Between Fiction and Innovation: Art as a Laboratory of the Real

What if art stopped being a space of representation and became a tool for manipulating life itself?

Today, some artists no longer limit themselves to painting, sculpting, or filming: they program genes, cultivate cells, modify DNA, 3D-print organs, or envision futures where humans share their wombs with pigs. This is no longer science fiction, not quite science either — and perhaps no longer "art" in the traditional sense. In this hybrid territory, halfway between laboratories and galleries, a new form of creation emerges: a speculative, critical art that uses scientific tools not to prove, but to question. These works deliberately blur the boundaries between the possible and the impossible, between ethics and absurdity, between innovation and dystopia.

From the Pink Chicken Project, where artists imagine marking the Anthropocene with genetically modified pink chicken bones, to Charlotte Jarvis' attempt to produce the first "female semen," and Ani Liu's provocative sculptures envisioning human pregnancies outsourced to pigs — these creations do not seek to embellish science: they divert it, challenge it, and reflect our own contradictions.

Far from the cliché of the "artist inspired by science," these projects reveal a field where art becomes a true laboratory of the real, capable of manipulating matter, life, and our visions of the future. A space where non-art becomes the only way to think the unprecedented.

Marking the Anthropocene in Pink: The Pink Chicken Project

Among these category-defying experiments, the Pink Chicken Project holds a unique place. At the crossroads of biotechnology, environmental critique, and political manifesto, this project offers nothing less than a genetic reinterpretation of our era — framed by a question as absurd as it is relentless: If industrial animal slaughter were tinted pink, would it be more acceptable, or simply more grotesque?

Created by the collective Nonhuman Nonsense in 2017, the Pink Chicken Project is far from mere visual provocation. Behind the striking image of a fuchsia-feathered chicken lies a credible scientific proposition: genetically modifying chickens so that their bones and feathers absorb pink pigment from cochineal. Enabled by CRISPR gene-editing technology, this modification aims to leave a colored, indelible trace in future geological strata — an artificial signature of the human era: the Anthropocene.

With nearly 60 billion chickens slaughtered annually, the project leverages this staggering figure to subvert scientific language into a radical artistic gesture: inscribing material proof of mass exploitation into geological time. Where past eras are marked by natural fossils, the Anthropocene could be symbolized by fluorescent bones — evidence of human voracity.

But the project goes far beyond environmental critique. By choosing pink — a culturally coded color associated with femininity, artifice, even kitsch — the artists introduce a layer of political irony. Pink becomes a subtle weapon against the supposed neutrality of hard sciences, a playful affront to the masculine, technocratic gaze imposed on life.

This work operates on multiple levels:

- Scientific: employing real biotech knowledge, proving that art can manipulate matter like any lab.

- Critical: forcing us to confront the absurdity of industrial animal production.

- Symbolic: transforming mass destruction into a paradoxical aesthetic trace — almost beautiful, yet deeply disturbing.

The genius of the Pink Chicken Project lies in this ambiguity: dystopia, ecological manifesto, satire, or chilling foresight of a future where humanity's legacy is the colored skeletons of its industrial victims?

By hijacking scientific tools, Nonhuman Nonsense exposes a harsh truth: innovation without conscience is an involuntary form of art, etched into the layers of time.

Rewriting Life: Charlotte Jarvis and Genetic Utopia

While the Pink Chicken Project embeds a critique of the Anthropocene in the bones of a domesticated species, Charlotte Jarvis pushes the fusion of art and science further: she doesn’t just mark life — she attempts to reprogram it, deconstructing the very foundations of our biological and social narratives.

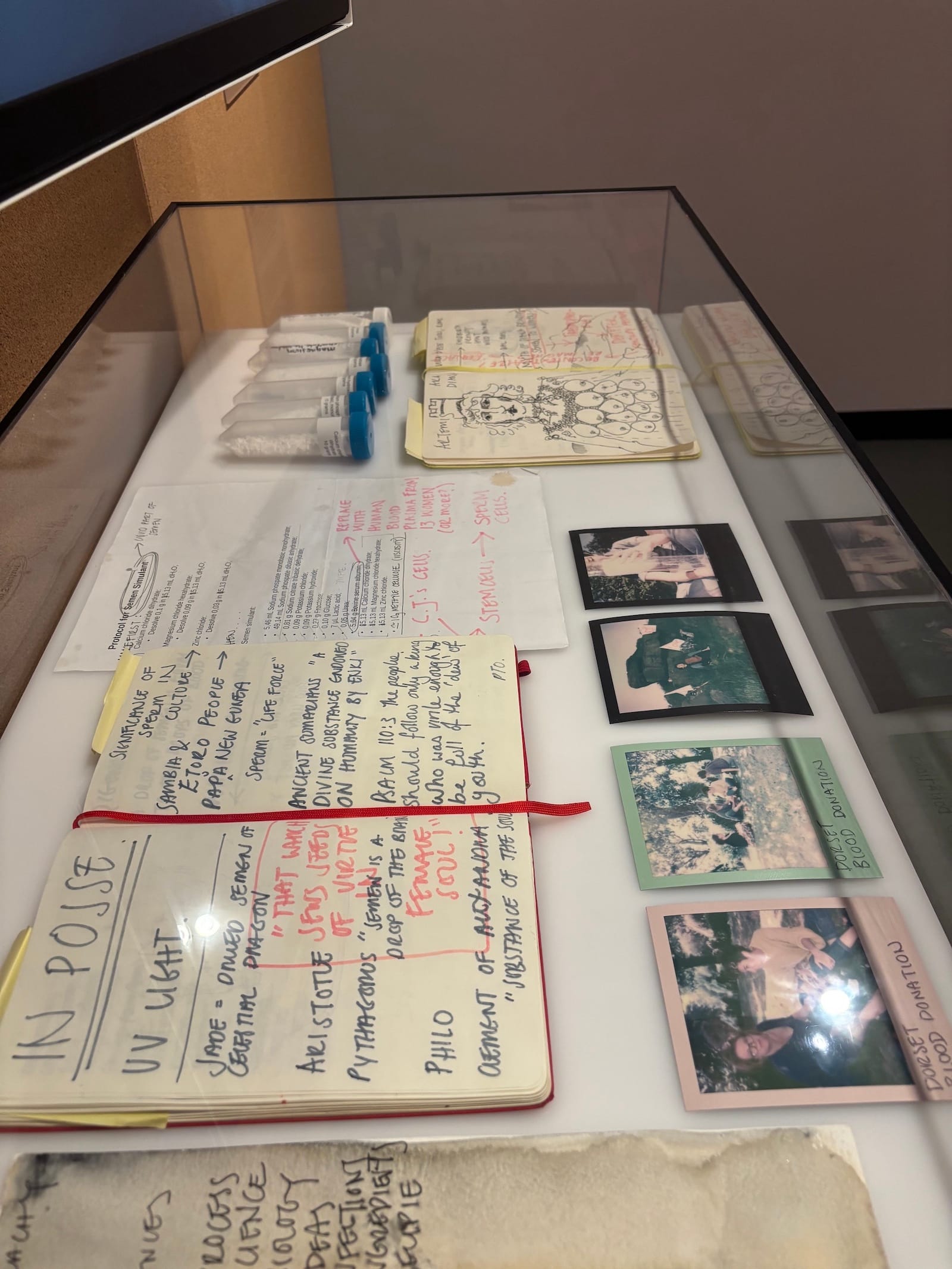

With her ongoing project In Posse: "Female" Semen (2017—), the British artist embarks on a bold and deeply political journey: producing semen from so-called "female" cells. Collaborating with biotech researchers, she works to create the first "female semen" — not as a scientific breakthrough, but as an artistic act of subversion.

Beneath the surface of a laboratory feat lies a radical challenge: What if patriarchy was also built upon a biology we thought immutable?

Jarvis doesn’t merely manipulate cells; she seeks to rewrite the scientific myth of masculinity as the sole active agent of reproduction. Her project raises unsettling questions:

— What if two women could conceive a biological child together?

— If semen lost its symbolic power as a totem of dominance, what would remain of inherited social structures?

A Laboratory Against the Language of Power

What stands out in In Posse is how Jarvis intertwines biotechnology with cultural rituals. She doesn’t just produce biological material; she embeds it within an anthropological reflection, invoking ceremonies inspired by ancient Greece (Thesmophoria) and involving women, trans, and non-binary participants from MIT. The work transcends scientific experiment — it becomes a collective performance, an embodied manifesto.

The quotation marks around "female" and "semen" highlight her focus on language, exposing the limits of binary categories imposed by science. Jarvis reveals that biology, far from being neutral, is saturated with social constructs, prejudices, and exclusions.

A Speculative and Reparative Work

In Posse exemplifies speculative artistic practice: not predicting the future, but opening possibilities, disrupting the status quo by showing that what appears "natural" is often the product of dominant narratives.

Once again, art assumes a role science cannot — or dares not — fulfill: asking uncomfortable questions, exploring alternative futures where technology serves liberation rather than control.

With this project, Charlotte Jarvis offers not just an artwork but an active utopia, where art becomes a tool for symbolic repair against the violences of patriarchy and biological essentialism.

Ani Liu: When Science Designs the Wombs of Tomorrow

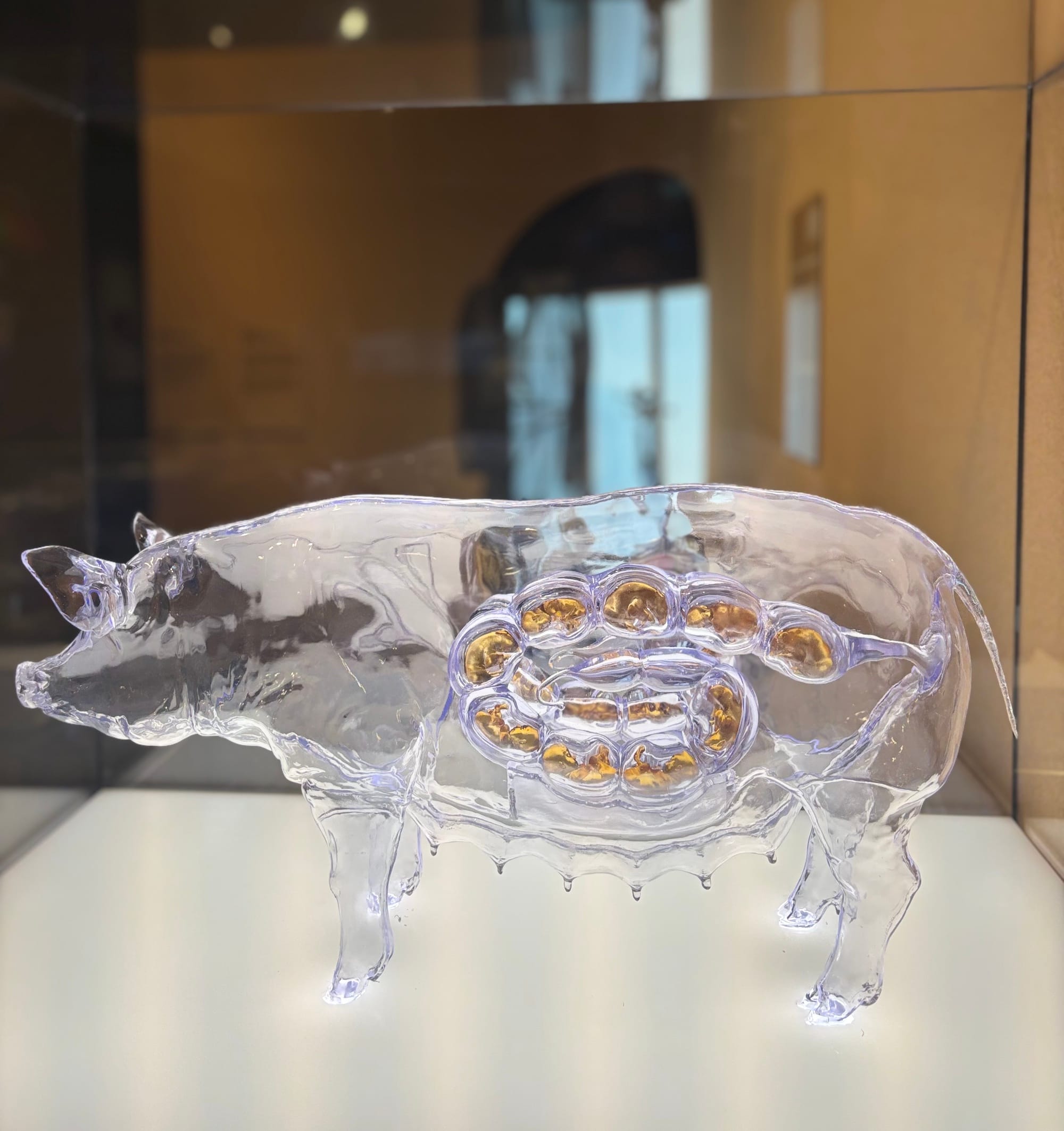

While some artworks play with the codes of biotechnology to reveal its absurdities or subversive potential, Ani Liu’swork delves into the heart of contemporary anxieties. With her project Pregnant Futures: The Surrogacy (2021), the artist materializes a disturbing question that contemporary science often prefers to avoid: how far are we willing to outsource life in the name of progress?

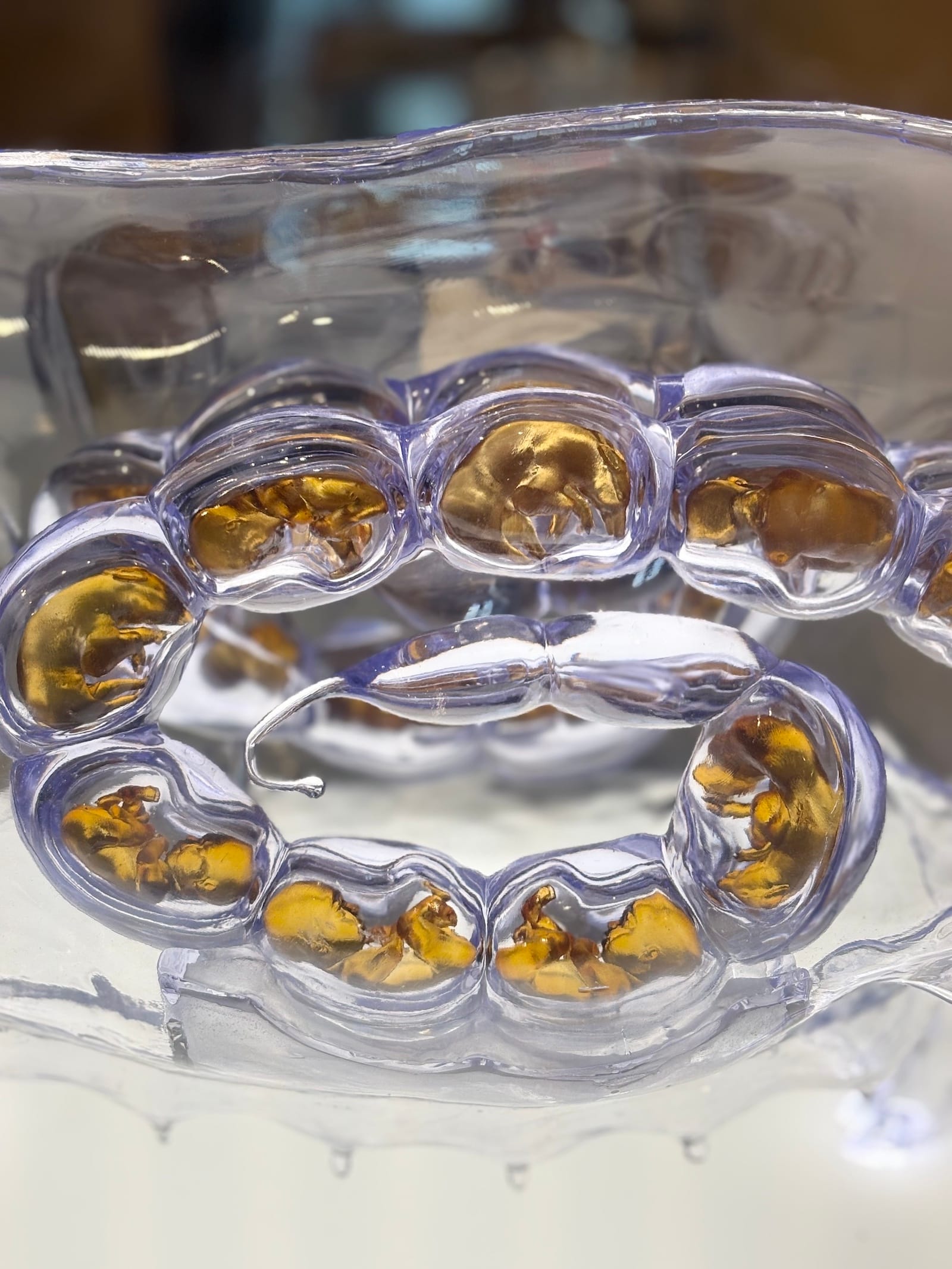

Confronted with this chilling sculpture of a translucent sow bearing 3D-printed human embryos in her womb, the viewer oscillates between fascination and discomfort. This is not science fiction — it is a plausible projection, grounded in ongoing research into interspecies pregnancy and artificial gestation.

Denouncing the Womb as a Commercial Space

Ani Liu’s artistic gesture is anything but gratuitous. She tackles a deeply sensitive issue: the commodification of the body, and more specifically, the female body. By staging a sow as a surrogate for human embryos, she draws a provocative parallel between animal exploitation and the ethical drift of surrogacy in a world where reproduction becomes a technical, outsourced, and optimized service.

The project raises direct and uncomfortable questions:

- Doesn’t technology, under the guise of emancipation, risk prolonging other forms of domination?

- Can we truly speak of progress when life is carried by machines or genetically modified animals?

- And above all: who decides how these innovations are used?

Provocation as Ethical Mirror

Rather than offering answers, The Surrogacy acts as a mirror held up to our time. The work exposes the coldness of techno-scientific discourses that treat reproduction as a mere problem to be solved — disconnected from social, cultural, and emotional realities.

Ani Liu, in true "artist-scientist" fashion, uses the materials of the future — polymers, 3D printing, biological modeling — to force the viewer to confront a plausible tomorrow: one in which pregnancy is no longer an intimate act, but a delegated, optimized, and perhaps even industrialized process.

What makes this project so powerful is its ability to physically embody a debate often confined to abstract spheres. While laboratories quietly pursue artificial wombs behind closed doors, Ani Liu gives these experiments form and visibility, injecting a critical and emotional dimension that science alone is unwilling — or unable — to bear.

Conclusion: When Innovation Extends Oppression — and Art Exposes It

These works captivate not merely because they wield science boldly, but because they unveil ancient mechanisms beneath the sheen of innovation: control over life, exploitation of bodies, commodification of femininity, and a vision of progress that crushes humanity beneath supposedly neutral technological narratives.

Since civilization's dawn, science has often been the silent ally of power structures — naturalizing hierarchies, confining femininity within biological definitions, justifying exploitation in the name of reason. Today, these dynamics resurface, disguised by terms like innovation, efficiency, and disruption. Whether in biotechnology, artificial intelligence, or biohacking, the core questions remain:

— Who controls these tools?

— Who benefits?

— And at whose expense?

AI promises to automate thought, but faithfully replicates sexist, racist, and classist biases embedded in human-generated corpora — shaped by centuries of linguistic patterns and structures steeped in patriarchal ideology. AI is not to blame; it acts as an algorithmic mirror, amplifying and spreading existing systems of domination under the guise of neutrality.

Biohacking dreams of augmented bodies — but according to whose standards, and serving which models of performance? Science advances, but often along the paths carved by and for the dominant.

In this context, art — at least the kind that ventures into these murky waters — becomes more than aesthetic space. It becomes counter-power.

These artists refuse to blindly celebrate technological promises. They question, divert, and expose the absurdity, shedding light on what science prefers to keep hidden: its social, political, and ethical implications.

What’s striking is that these works reject the classic utopia of "liberating progress." Instead, they reveal that innovation can be a sophisticated extension of oppression if left unchecked by critical thought.

In a world saturated with technological narratives, where humans risk being reduced to adjustable variables, these artistic practices remind us that creation is not here to decorate innovation — it exists to challenge it, to give a face to the invisible, a voice to the instrumentalized, and a conscience where science claims amorality.

Ultimately, this territory between art and non-art may be the last space where fundamental questions can still be asked:

What is humanity?

What is freedom, when even our bodies can be reprogrammed?

And what remains of femininity, when technology pretends to transcend it while reproducing its oppressions?

These works offer no answers — but they force us to see. And in a world sleepwalking toward its own dystopias, that is already an act of resistance.

If you’d like to explore the topic further, please refer to the bibliography below.

📚 Bibliography / References

🔬 Art & Science / Speculative Practices

- Wilson, Stephen. Art + Science Now: How scientific research and technological innovation are becoming key to 21st-century aesthetics. Thames & Hudson, 2010.

- Wilson, Stephen, Information arts, Intersection of Art, Science and Technology, 2002.

- Zurr, Ionat & Catts, Oron. "The Tissue Culture & Art Project".

👩🚀 Feminism, the Body, and the Biopolitical

- Preciado, Paul B. Testo Junkie: Sex, Drugs, and Biopolitics in the Pharmacopornographic Era. The Feminist Press, 2013.

- Haraway, Donna J. Simians, Cyborgs, and Women: The Reinvention of Nature. Routledge, 1991.

- Braidotti, Rosi. Posthuman Feminism. Polity Press, 2022.

- Firestone, Shulamith. The Dialectic of Sex: The Case for Feminist Revolution. Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2003.

🧠 Technology, AI & Biohacking

- Noble, Safiya Umoja. Algorithms of Oppression: How Search Engines Reinforce Racism. NYU Press, 2018.

- Benjamin, Ruha. Race After Technology: Abolitionist Tools for the New Jim Code. Polity, 2019.

- Zylinska, Joanna. AI Art: Machine Visions and Warped Dreams. Open Humanities Press, 2020.

🌍 Anthropocene, Ecology & Post-Nature Art

- Demos, T. J. Against the Anthropocene: Visual Culture and Environment Today. Sternberg Press, 2017.

- Morton, Timothy. Hyperobjects: Philosophy and Ecology After the End of the World. University of Minnesota Press, 2013.

- Parikka, Jussi. A Geology of Media. University of Minnesota Press, 2015.