What if Hitler Had Been Accepted to Art School?

A Visual Journey Through the Boundaries of What Is Not Art

When does an image cease to be art? Is it a matter of lacking innovation, vision, or is it the nature of the creator that disqualifies it?

It is widely known that before Adolf Hitler ( became the dictator history remembers, he aspired to be an artist. Twice he applied to the Academy of Fine Arts in Vienna. Twice he was rejected. That moment has since been mythologized as a historical turning point. And from there, a recurring question has emerged—sometimes in jest, sometimes in solemn curiosity: What if he had been accepted?

But beyond the moral or historical fantasy lies a more delicate question: What about the paintings themselves? These works, often dismissed as curiosities or scandalous relics, invite us to reflect not only on history but on art itself. Do they belong to art history, or do they fall outside its boundaries?

A Question of Legitimacy

In his novel The Alternative Hypothesis (La part de l’autre), Eric-Emmanuel Schmitt imagines an alternate reality in which Hitler is accepted into art school. He wrote:

“On October 8th, 1908, the man history would come to know as Hitler becomes Adolf H., a student of the Fine Arts. And the world breathes.”

This quote underlines how a rejection—personal, institutional, seemingly trivial—can become a rupture in the course of history. Would've that been enough to change the course of History? "What if you could go back in time and kill Hitler as a child?” I often heard the question posed—sometimes as a dark joke, other times more seriously, as though a single act could prevent a global catastrophe. But perhaps we give too much credit to One man. He didn’t invent hatred; he amplified it.

Long before Hitler, antisemitism was already institutionalized across much of Europe. In France, during the infamous Dreyfus Affair, this hatred became tragically visible. In 1898, Émile Zola wrote his open letter J’accuse…! to the President of the Republic, denouncing the false conviction of Jewish officer Alfred Dreyfus and the structures that enabled it.

“So there you have it, Mr. President, the facts that explain how a miscarriage of justice could occur; and the moral evidence—Dreyfus’s financial situation, the absence of motive, his constant cries of innocence—show him clearly as the victim of the extraordinary imaginings of Commandant du Paty de Clam, of the clericalist circles in which he moved, and of the hunt for ‘dirty Jews’ that dishonors our era.”

Zola’s words were not only a defense of one man but an indictment of a culture willing to sacrifice truth for prejudice. That “hunt for ‘dirty Jews,’” as he called it, would not end with Dreyfus. It would find new forms, new names, new uniforms. By the time Hitler emerged, the ground had already been laid—fertile, toxic, and ready.

Apologies for the detour — yet perhaps it was necessary. Sometimes, to understand the weight a single brushstroke can carry (or fail to carry), one must look at the wider canvas of history. Now, let us return to the paintings themselves.

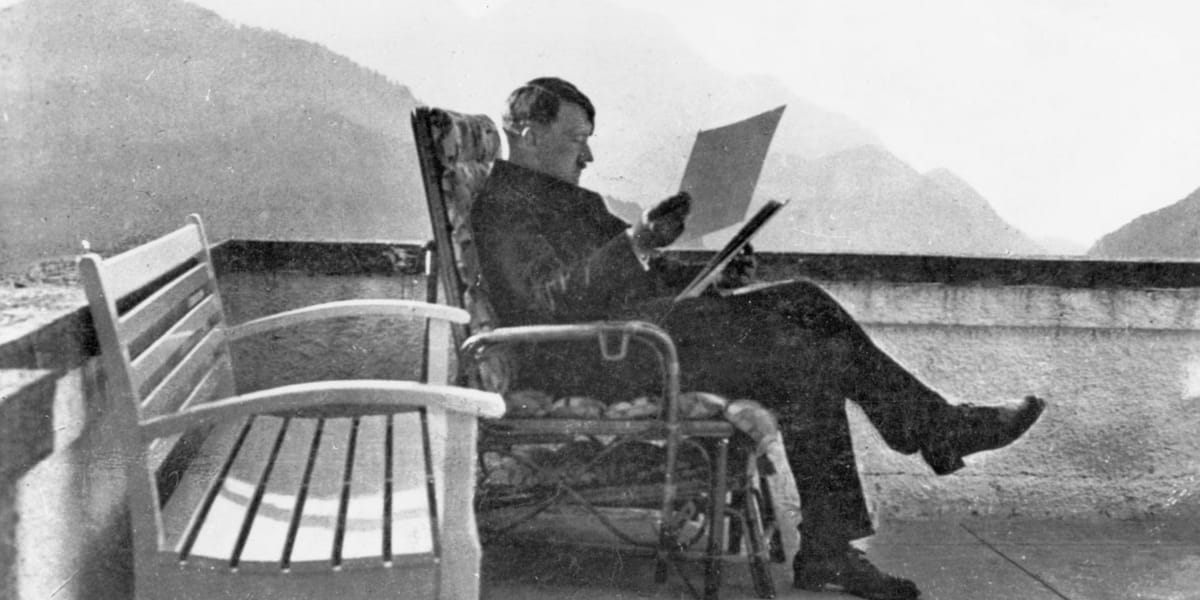

So was the rejection unfair? A closer look at Hitler’s work suggests not. His teachers criticized his lack of imagination, his inability to convincingly depict the human figure, and his rigid academicism. These critiques remain relevant today.

Hitler, 1889-1945 (age 56 years): Well-Executed Works, But Without Vision

Two of Hitler’s watercolors illustrate this point clearly: one shows a courtyard in Munich, the other a bouquet of flowers in a vase. The perspective is correct, the brushwork competent, the color choices subdued. But nothing surprises. Nothing challenges. Nothing lives.

These are the works of someone eager to please an institution, not someone driven by a need to say something new. And that’s perhaps the essential difference: imitation versus invention. Order over expression. Decoration over disruption.

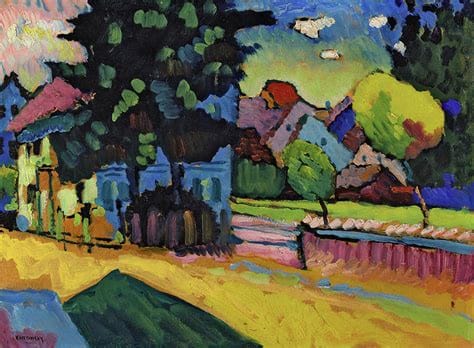

It is all the more striking that Adolf Hitler, while painting lifeless watercolors of courtyards and flowers, was living at the very heart of a continent in artistic revolution. Around him, in the very same decades, artists like Gustav Klimt and Egon Schiele were transforming the Viennese art world with sensuality, distortion, symbolism, and psychological depth. Meanwhile, just across the border in Munich and Murnau, Wassily Kandinsky was breaking down form itself, inventing a new visual language rooted in abstraction and spiritual resonance.

These artists were not separated from Hitler by centuries or geography—they were his contemporaries, his near neighbors, shaped by the same atmosphere of collapse and transformation. And yet, Hitler’s work seems completely oblivious to its own Zeitgeist and disconnected from the Weltanschauung — the worldview — that defined the modernist moment. His style, stuck somewhere between provincial realism and a diluted Impressionism, looked backwards rather than inward or forward.

In a moment when art was questioning the very nature of perception and experience, Hitler’s paintings were trying, still, to get the bricks straight. In a sense, his paintings are not just conservative; they are anachronistic. It’s as if they arrive a half-century late, unaware of the storm gathering around them.

Kandinsky, 1866 - 1944 (age 77 years): Painting as Inner Resonance

At the same time, in the same region, Wassily Kandinsky was painting the Bavarian town of Murnau—not with architectural precision but with emotional intensity. His houses sway, his colors sing, his skies pulse. Kandinsky wasn’t describing the world—he was interpreting it.

Hitler painted what he saw. Kandinsky painted what he felt. And perhaps art, at its core, is a matter of that interior shift. A gesture from the visible toward the invisible.

Schiele, 1890 - 1918 (age 28 years): The Violence of Introspection

Egon Schiele, another Viennese artist of the early 20th century, offers a striking counterpoint. His figures are contorted, his lines broken, his portraits brutal in their honesty. Schiele painted the body not as it should be, but as it is—fragile, erotic, grotesque, alive.

Where Hitler avoids the human form entirely, Schiele confronts it obsessively. One hides complexity, the other exposes it. Schiele disrupts the classical ideal. Hitler clings to it.

Schiele’s work may be disturbing—but it disturbs because it has something to say.

Klimt, 1862 - 1918 (age 55 years): Ornament as Language

And then there is Gustav Klimt, the master of Viennese symbolism. Klimt’s paintings are ornate, sensual, radiant with gold and ambiguity. But they are not merely decorative—they are symbolic. His women, his patterns, his glances—all speak to desire, power, mortality.

In Klimt’s work, surface becomes meaning. In Hitler’s work, surface is just surface. There’s no dialogue with history, no mystery, no excess.

Klimt gives form to enigma. Hitler stays in the safety of formality.

Painting as Validation?

Was painting, for Hitler, a form of self-validation? A bid for social legitimacy? In Schmitt’s fictionalized account, art might have saved him. But art, in its truest sense, cannot emerge from a need for acceptance alone. It must be born of necessity—inner urgency, spiritual unrest, vision.

Without that, painting becomes nothing more than execution.

Art or not Art?

Hitler’s paintings raise a difficult and essential question: What is not art? Can technique alone make something art? Or does it require a perspective—a rupture, an invitation, a disturbance?

Can we separate the artist from the work? Or are there cases where the artist overshadows the work entirely?

This article doesn’t seek to resolve these tensions, but to open them. Perhaps art begins where imitation ends. Perhaps art and not art are not opposites, but two permeable spaces—blurred at the edges, defined less by rules than by intention, risk, and resonance. And in those uncertain zones, we might learn as much from what fails to move us as from what does.

What remains is the question—not just of what art is, but what we expect it to be, and what we refuse to let it become.

Bibliographical References

- Schmitt, Eric-Emmanuel. La part de l’autre. Albin Michel, 2001.

- Zola, Émile. J’accuse…! L’Aurore, 1898.

- Kandinsky, Wassily. Concerning the Spiritual in Art. Dover Publications, 1977.

- Nebehay, Christian M. Gustav Klimt: From Drawing to Painting. Harry N. Abrams, 1994.

- Kallir, Jane. Egon Schiele: The Complete Works. Harry N. Abrams, 1998.

- O'Connor, Anne-Marie. The Lady in Gold: The Extraordinary Tale of Gustav Klimt's Masterpiece, Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer. 2015.